Independent: 1912-1928, 1930-1931, 1950

American Negro League: 1929

East-West League: 1932

Negro National League II: 1933, 1935-1948

Negro American Association: 1949

Tombstone

Born: 1912 (Murdock Grays become Homestead Grays)

Folded: May 22, 19511Grays Out of Baseball, INS, via, The Vindicator, Youngstown, OH, May 23, 1951

First Game: 1912

Last Game: November 4, 1950 (W 9-0 @ Mobile All-Stars)

League Titles: 11 (1931, 1937, 1938, 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945, 1948, 1949)

Negro World Series Championships: 3 (1943, 1944, 1948)

Ballparks

Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, PA: (1917

Opened: June 30, 1909

Closed: June 28, 1970

Demolished: July 28, 1971

Greenlee Field, Pittsburgh, PA: 1932-1937

Opened: 1932

Closed: 1938

West Field, Munhall, PA: (1937-1949)

Opened: 1937

Rebuilt: 2015

Griffith Stadium: 1940-1950

Opened: July 24, 1911

Closed: September 21, 1961

Demolished: January 26, 1965

Ownership

Owners:

Cumberland Posey and Charly Walker:1920-1934

Cumberland Posey & Rufus “Sonnymann” Jackson: 1934-1946

Rufus “Sonnymann” Jackson: 1946-1949

Seward “See” Posey: 1949-1951 (Business Manager)

Background

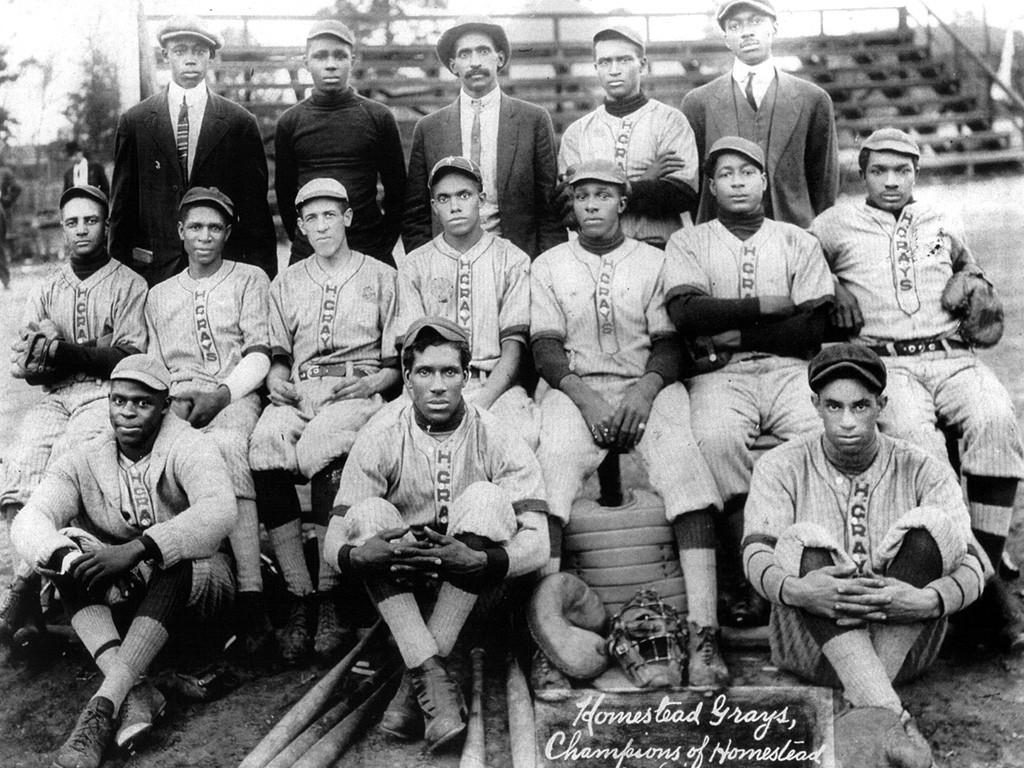

The Homestead Grays were one of Negro baseball’s greatest teams and are still well known today. An independent, barnstorming team for much of its existence, the club won 11 league titles and three Negro World Series championships.

The club’s roots go back to the turn of the 20th century and a team called the Blue Ribbons. Based in Homestead, PA, a suburb of Pittsburgh, the Blue Ribbons team was a recreational baseball club composed of black steelworkers, most of whom worked in the local U.S. Steel plant.

They later became known as the Murdock Grays and gained the backing of local black businessmen. In 1911, Cumberland Posey joined the team as an outfielder.

A star is born

Posey worked as a clerk for the Railway Mail Service, but he had greater ambitions. He was the son of one of the richest black businessmen in Pittsburgh and had been a star athlete at Penn State. He made an immediate impact on the Grays while working and continuing his education at nearby Duquesne University. There, he also excelled in basketball.

In 1912, Posey took an active role in running the Mudock club, which was renamed the Homestead Grays. By 1917, he was team captain, field manager, and booking agent. Though still an amateur squad, the club played home games against teams from Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia at Forbes Field, home of the National League’s Pirates.

Taking control

Posey finally quit his day job in 1920 when he and teammate Charlie Walker bought the Grays. Running the team became a full-time job, and the duo continued to build a winning side. Already well known throughout the country, the Grays were invited to join the first organized, major league-level black baseball circuit, the Negro National League (NNL) that same year.

The NNL was organized in Kansas City by Chicago American Giants star pitcher and owner Rube Foster. The Grays seemed like a great fit for the new league, but Posey turned Foster down. It was much more profitable, Posey reasoned, to keep the Grays a barnstorming team.

To further bolster the Grays, Posey regularly poached players from the NNL, as well as the East-West League formed in 1923. The Grays biggest catch, as it were, was “Smokey” Joe Williams, who helped propel the team to a 43-game win streak in 1926.

Posey hung up his cleats after the 1926 season to focus on managing the ballclub on and off the field. The team didn’t miss a beat, though. The 1930 Grays were one of Posey’s best teams, with legends such as Oscar Charleston, Judy Johnson, and Josh Gibson. In 1931, they got even better, when they added Willie Foster (Rube’s half-brother), Ted Page, and Ted Radcliffe. The latter’s nickname was “Double Duty,” as he played pitcher and catcher (though not at the same time). More stars arrived in 1932, including James “Cool Papa” Bell, Ray Browne, Willie Wells, and Newt Allen.

It was an extremely talented but expensive roster, and Posey felt the pinch. The Depression had impacted attendance, as fewer people could afford to attend games. As a solution, the league-adverse Posey formed the East-West League to fill the gap left by the demise of the NNL in 1931.

It didn’t work. The East-West League didn’t even complete its inaugural season. To make matters worse, the crosstown Pittsburgh Crawfords were signing Posey’s best players. Ironically, this was at a time when the Grays were using the Crawfords’ ballpark, Greenlee Field, for some home games.

Any port in a storm

William A. “Gus” Greenlee, the Crawfords owner, organized a new Negro National League (NNL II) for the 1933 season. The Grays joined but dropped out after a dispute over player raiding by the other clubs. In 1935, they were back in the NNL II, with a new co-owner.

Rufus “Sonnyman” Jackson became Posey’s partner. He was the complete opposite of the Grays’ longtime player, manager, and owner in many respects. While Posey came from the upper crust of black society, refereed high school basketball games, served on the local school board, and wrote a column for the local newspaper, Jackson’s business ventures were of a more nefarious nature.

Still, the new co-owner pumped money into the team, which allowed it to settle outstanding payroll and purchase a new bus. More importantly, it gave Posey the resources to sign new players to replace the ones signed away by other teams or who had retired.

The team’s fortunes gradually improved, and by 1937, they won the pennant, the first of nine NNL II titles captured by the Grays. Success on the field, however, did not translate into success at the gate. Hefty salaries and low attendance meant red ink for the Grays. This, despite the relocation to Toledo of their crosstown rivals, the Pittsburgh Crawfords for the 1939 season.

A capital idea

In July 1939, in the middle of a pennant-winning season, the Grays floated the idea of playing their home games in Washington, D.C. On February 3, 1940, it became official as Posey and Jackson announced their intention to play “home games” (quotes added by the press) at Griffith Stadium in the nation’s capital.2Grays to Play in Washington, The Afro-American, Feb. 10, 1940

The team didn’t abandon Pittsburgh, though, as some games were still scheduled at Forbes Field and West Field in suburban Munhall. West Field is still in existence today as a small, modern ballpark and is used by Carlow University, a small Catholic college. Steel Valley High School also uses the field. Home plate is still in the same spot.

Washington was a great second home for the team. As author Brad Snyder points out in his book Beyond the Shadow of the Senators, Washington had a large, highly educated black population that loved baseball. It was also easily accessible by rail to other large cities with Negro baseball teams, such as Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York.

Even in D.C., the club was officially called the Homestead Grays. The press often referred to them as the Washington-Homestead Grays, but in any case, their winning ways continued as the team won the NNL II pennant in 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943, 1944, and 1945.

The dynasty

Starting in 1942, the Negro World Series, last played in 1927 between the winners of NNL (I) and the East-West League, was revived. This time it pitted the champions of the NNL II against the Negro American League (NAL) pennant winner. The Grays lost the 1942 series to the Kansas City Monarchs. They won in 1943 and 1944 before losing to the Cleveland Buckeyes in 1945. In 1946, the Grays finished in third place. Just before the start of that season, Cumberland Posey passed away at the age of 55. At that point, “Sonnyman” Jackson became the sole owner of the Grays.

The year 1947, of course, marked the beginning of the end for the Negro leagues. On April 5th of that year, Jackie Robinson broke the color line when he debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Later that season, on July 5th, Larry Doby started for the Cleveland Indians. Soon, other clubs began to sign top black ballplayers. As such, 1948 was the last year for the NNL II. The Grays were the league’s final pennant winners.

Staying the course

Four clubs from the NNL II joined the NAL, which soldiered on as a minor league until 1962. The Grays at first opted fold in December. The team’s players were went to other NAL clubs in dispersal draft in February, 1949 .3 Buckeyes to Louisville in NAL Shift, Grays Top Talent Goes in Draft, The Afro American, Feb. 19, 1949

However, the Grays quickly reformed with a new roster and joined the Negro American Association (NAA), which had been in operation as a minor league since 1939. That was the doing of See Posey, Cumberland’s brother, who operated the team after “Sonny Man” Jackson passed away just before the start of the 1949 season.

Even without their star players, the Grays rolled over the entire NAA and won the pennant. The league didn’t return for the 1950 season, though several surviving clubs formed a new circuit. The Grays went back to barnstorming but also obtained association status in the Negro American League. That meant they could play NAL teams but would not be listed in the league’s official standings.

The end of an era

The final home game for the Grays was played in Washington at Griffith’s Stadium on August 6, 1950, as the second half of a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Stars.4Satchel Losing Pitcher as Grays Down Stars, The Afro-American, Aug. 12, 19504 The Grays won the first game 7-1 and the nightcap 12-2.

They closed the regular season on Sunday, September 10, 1950 in Parkersburg, WV. There, they defeated the Parkersburg Stars 7-2 to end with a record of 100 wins against 26 losses for the season.5Grays Ends Season with 100 Wins, The Baltimore African-American, Sep. 16, 1950 Less than a month later, the Grays announced a barnstorming tour through the South to begin in October. They only played 10 when bad weather and small crowds forced them to cancel the remaining 12 games.

The very last Homestead Grays game was played in Mobile, AL, against a team called the Mobile All-Stars. The Grays won 9-0.6Homestead Grays Drop Fall Tour, The Afro-American, Nov. 18, 1950 The end officially came on May 22, 1951, when See Posey made it official and announced to the press that the team had folded.7Grays Out of Baseball, INS, via, The Vindicator, Youngstown, OH, May 23, 1951

Our friends at the Good Seats Still Available podcast did an episode on Cumberland Posey and the Homestead Grays:

Additional Source: Beyond the Shadow of the Senators, The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball by Brad Snyder, Contemporary Books, 2003. ISBN: 0-07-140820-7